|

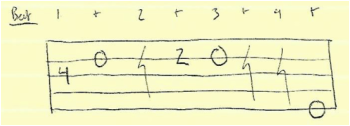

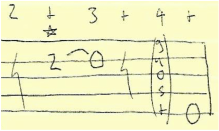

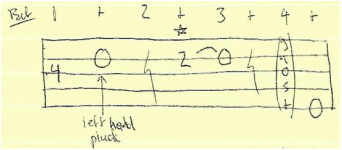

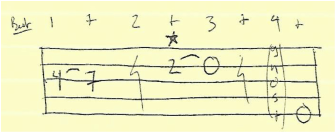

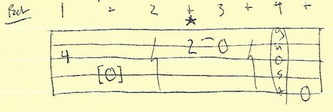

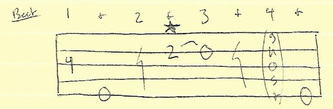

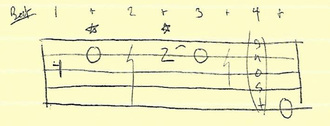

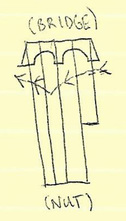

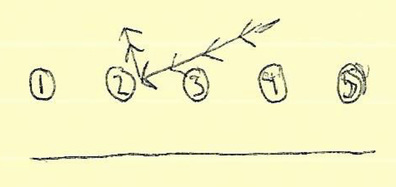

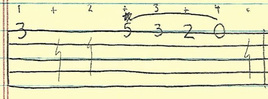

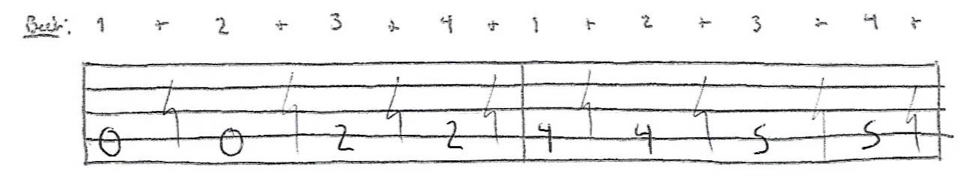

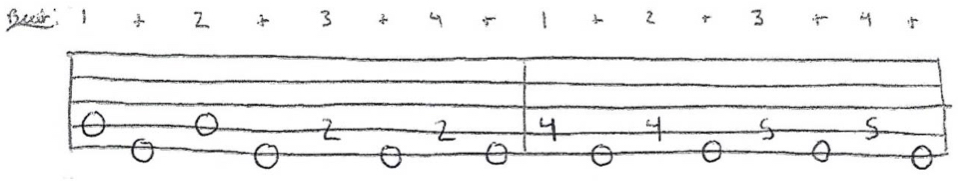

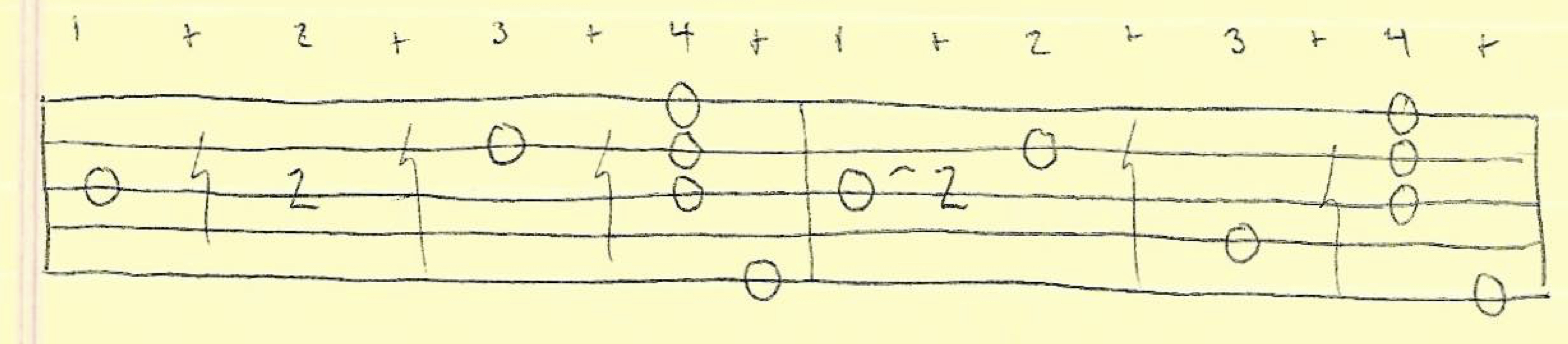

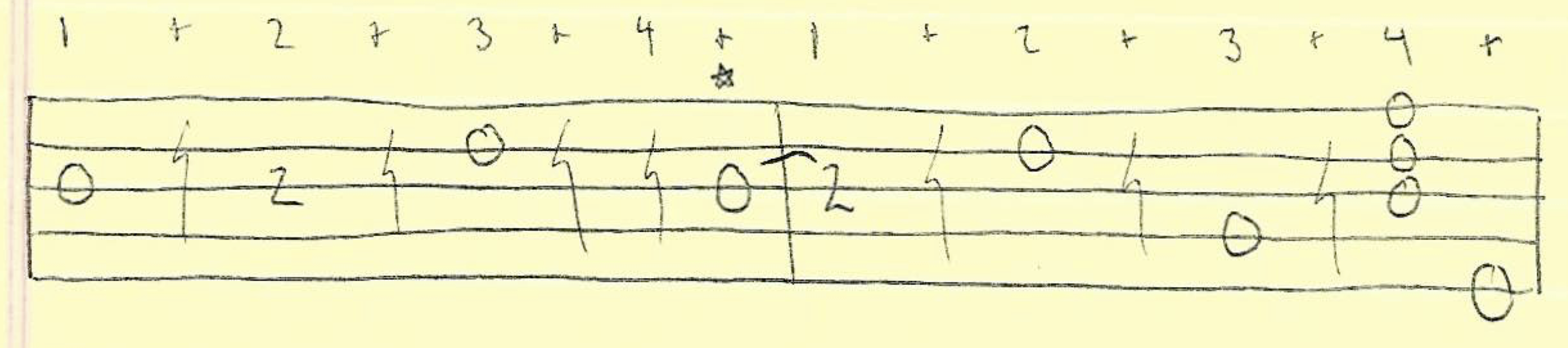

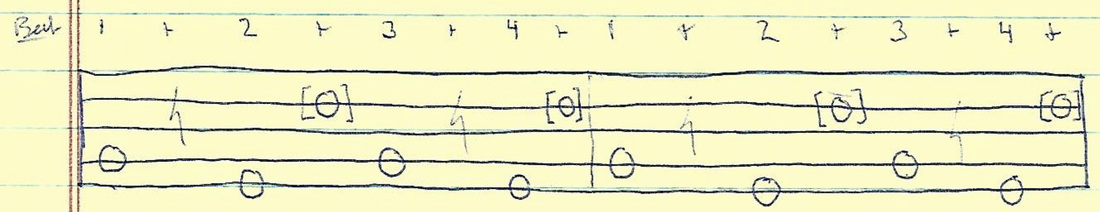

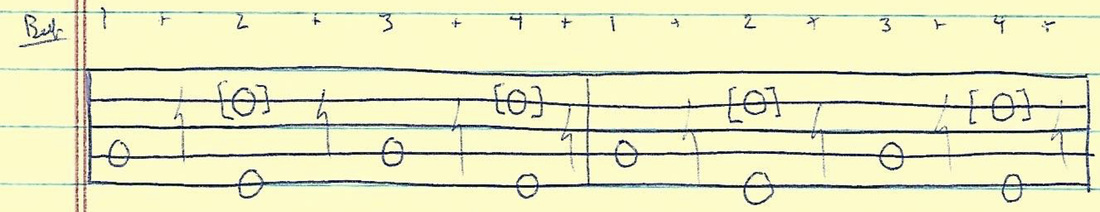

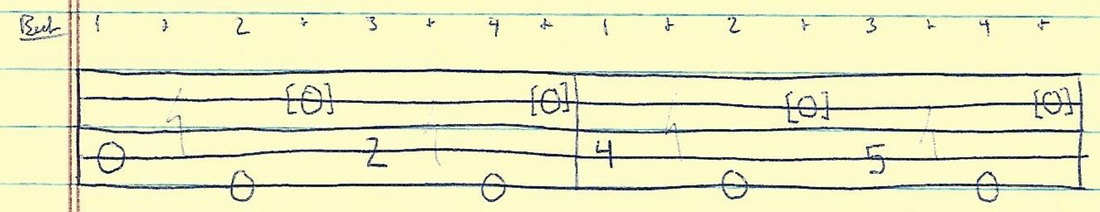

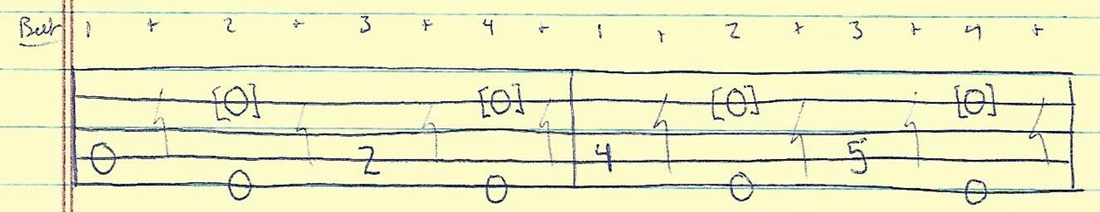

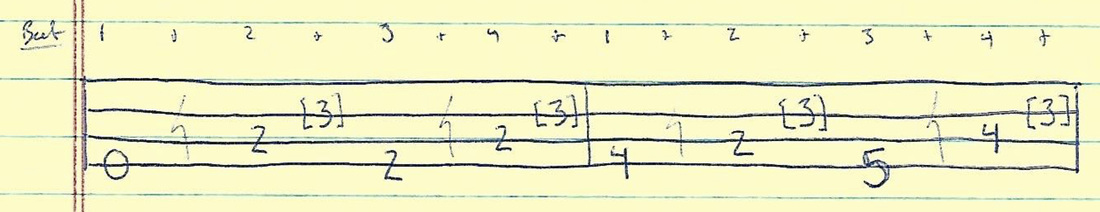

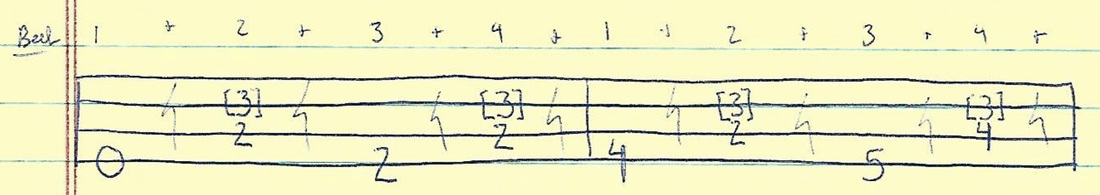

In last weeks post (here), I broke down the rules that govern "Right Hand Stride" in clawhammer banjo playing and gave an example of breaking these rules to catch the melody that the fiddle plays in "Angeline the Baker." This week I'll build on that approach and show you another trick for breaking right hand stride using the Jay Ungar tune "Round the Horn." Before I get too deep into today's post, lets review the aforementioned rules: Rule 1 for maintaining right hand stride: The index finger of the right hand moves towards the strings on every beat; the thumb never plays notes on the beat. Rule 2 for maintaining right hand stride: The index finger is never used to play notes between beats; these notes should be played with the thumb of the right hand, with a left hand pluck, or by hammer-ons/pull-offs from notes played on preceding beats. Rule 2a) if the note on an "and" beat is on a lower string than the preceding note (or if the preceding beat contains a brush, cluck, or ghost note) this note should be played with the thumb of the right hand, or by plucking the string with the left hand. Rule 2b) if the note on an "and" beat is at a higher fret of the same string of the preceding note, this note should be played with a hammer on. Rule 2c) if the note on an "and" beat is at a lower fret of the same string of the preceding note, this note should be played with a pull off. Rule 2d) if the note on an "and" beat is on a higher string than the preceding note, this note should be played by plucking the string with the left hand. Now a bit on the tune: fiddler Jay Ungar is best known for writing "Ashokan Farewell," which was prominently featured in Ken Burns' documentary TV series The Civil War; I'm not too embarrassed to say that I assumed "Ashokan Farewell" was a genuine Civil War-era fiddle tune when I first heard it, though Jay Ungar actually wrote it in the 80's. "Round the Horn" is another Jay Ungar original that frequently makes it way into Old Time jams alongside the classics. I first heard it at a local jam after moving to Michigan and its one of those rare 4/4 fiddle tunes like "Coleman's March" and "Seneca Square-dance" that actually sounds best at a moderate tempo. The guitarists at the jam love "Round the Horn" because, though the tune is in G major, they end both the A and B parts on a heavy-handed E minor chord; definitely makes for a fun tune! All of that being said, "Round the Horn" doesn't really "fall naturally" on clawhammer banjo, primarily due to right hand concerns. Figure 1 shows a phrase from the A part that provides an example of what I'm talking about. Note that as with the majority of my G tunes, I play "Round the Horn" in Old G (gDGDE; post on the logic behind this decision here): Figure 1 - A tricky phrase from the A part of "Round the Horn" by Jay Ungar. Lets start by talking about the last three notes of the phrase (i.e. the stuff that starts on the 2+ beat above). Based on what I talked about last week (once again, here) you can probably guess how I'll handle this stuff: Figure 2 - Breaking stride in the 2nd half of the "tricky phrase' shown above. The star above the staff indicate that this note should be played with the index finger; this note breaks right hand stride. To review, if we were playing the phrase in Figure 2 "in stride" we'd put a ghost note on beat 2, use a drop thumb to get the note on the following "and" beat (beat 2+), and use our index finger to play the note on beat 3. However, all of these left hand shenanigans strike me as a bit of unnecessary pageantry; in a move similar to what I did in Figure 8 last week, I've chosen to use a fairly standard pull off that breaks stride by starting between beats (i.e. on an "and" beat). Now, lets take a look at the first two notes in Figure 1. To play these notes "in stride" we'd play the first note with our index finger (Rule 1) and the second note with a left hand pluck (Rule 2d). See Figure 3 below: Figure 3 - using a left hand pluck to avoid breaking stride in the second note of Figure 1. I can tell you're impressed with my creative solution for designating when to use a left hand pluck. As I mentioned last week, I don't really use left hand plucks in my playing if I can avoid them. However, I mind them less when the offending note and the one that precedes it are both open strings, because the left hand is basically sitting there un-occupied on the preceding beat, available for plucking when needed. In the case shown in Figure 3, you're holding down a fretted note on the 1 beat and then you've got to figure out how to pluck the open 2nd string on the 1+ beat. I have yet to mention the left hand position for any of the tabs above (click here if you don't know what I'm talking about...): this tab is best played by covering frets 2-5 with the index, middle, ring and pinky fingers of your left hand without skipping a fret. Using this hand position, you'd be holding down the note beat 1 with your ring finger, making your index available for plucking the string on the 1+ beat. While this can be done, I do find it a bit awkward; also I should point out that 2 fretted on adjacent string notes become really difficult to play in this manner. Before talking about how I break the rules to play these notes, let me give you a few more non-rule breaking alternatives (I should mention here that the note on the 1+ beat is a "D"....just easier to talk about it this way): Figure 4: Using a hammer-on to get the D on the 1+ beat. Figure 5: Using a drop thumb to play a low octave D on the 1+ beat. The brackets indicate that the note should be played with the thumb of the right hand. Figure 6: Adding in a 5th string pull instead of playing the D on the 1+ beat. I've used all of the ideas from Figures 4-6 in my playing at some point. Figure 4 has the advantage of actually staying true to the melody. However, it involves a slightly obnoxious left hand position shift (you'd play the 4th fret with your index finger and the 7th fret with your pinky) followed by a run back down the neck to get the note on the 2+ beat. Figure 5 actually involves an alteration of the melody by moving the D down an octave, where it is easily reached via a drop thumb. This actually sounds OK when you're playing in unison with a fiddler, but its a little strange when playing alone. Figure 6 is kind of an admission that the subtleties of this melody are beyond our grasp as clawhammer players; the 5th string pull just fills melodic space. But, we can simply break the rules and get the note we really want as follows: Figure 7 - Breaking stride to get the D note on the 1+ beat. As with the note on the 2+ beat, the star above the staff indicates that this note should be played with the index finger, thereby breaking right hand stride. So last week (sigh, here), I introduced a particularly notey phrase from "Temperance Reel" and toyed with the idea of playing every note with the index finger of the right hand. However, I mentioned that this approach would necessitate moving your hand twice as fast as indicated by Rule 1, which kind of excludes it from being useful at high speed. Playing 2 eighth notes in a row (as shown in Figure 7) seems to have this same issue - so how do we solve this? We pluck both strings in a single movement. To explain: Figure 8 - A poorly drawn explanation of how to accomplish our latest rule breaking maneuver (shown in Figure 7). For the figure on the left, pretend you're looking down your banjo neck from the nut to the bridge...and that every part of the banjo other than the strings and bridge has disappeared for some reason. For the figure on the right, the circled numbers represent cross-sections of strings 1-5 and the line at the bottom represents the fingerboard. If you look at the left side of Figure 8, you'll see a "big picture" explanation of what you're doing for the first two notes of Figure 7. While the right hand motion of a clawhammer player goes "downward" towards the strings when plucking, typically nothing happens on the way back up (in fact, you've likely trained yourself to avoid undue noises when re-setting your hand for the next on-beat strike). However, you could use the "upward" portion of this motion to pluck the adjacent string and get another note! In this sense, you're almost not breaking stride....but I'll continue to talk about it that way. This does seem like it requires a high amount of right hand control however - how would you do this "in the moment?" The right side of Figure 8 gives you a trick to rein in your right hand motion and accomplish this pretty simply: aim your initial downward strike towards the next string over (in this case the 2nd string) - pretend like this string is a wall and make sure you hit it! You'll strike the 3rd string along the way to this collision, then simply lift up your hand while continuing your momentum and you'll end up plucking the second string as well. This pluck will likely be fairly light in comparison to the note on the 1 beat, but thats just fine! Amazingly, I've gotten this move to the point that I can even do it at fairly high speed - I'm sure you can get there too! I guess its time to introduce the actual tab here: Unfortunately, I'm not in a position to get any recording done this week so there's no audio to add here; my apologies, I'm going to try and add a recording at a later date. Hopefully the dissection of Figure 1 will help you get through the tab however: that phrase appears in the 2nd measure of the A part, and the 2nd and 4th measures of the B part. There is other "rule breaking" peppered throughout the tab as well, most of it similar to what we did with "Angeline the Baker" last week. However, there is one more bit of rule breaking in the 5th measure of the B part that I'll highlight before I go: Figure 9 - 3 pull-offs in a row in "Round the Horn." So, we break stride in Figure 9 by using our index finger on the 2+ beat, but we continue to break the rules by stringing 3 notes behind this first note in a series of pull-offs; during this move, my right hand just stops moving altogether while my left hand does all the work. It would be easy to break this phrase in half by striking the 1st string on both the 2+ and 3+ beats and using pull offs to get the notes on the following beats, and I'd encourage you do try that out as well. However, when I play this tune, the series of pull-offs in Figure 9 just kind of happens naturally; therefore I thought I may as well put it in the tab : )

I've got a fairly busy Sunday (I'm down in VA with family for thanksgiving) so I thought I'd post a day early this week - hope anyone reading this had a great holiday!

2 Comments

I've always thought that there are two important steps to mastering a creative pursuit (like playing an instrument): first you figure out the "rules" of your subject, then you figure out when to break them. In learning the rules of a given subject, you place yourself in the arena with all of those who have come before you and you develop a critical eye for judging your own work. However, its in step two that innovation occurs. While many newcomers to a given field set out to "break the rules" from day one, I find that innovation contextualized by tradition (i.e. innovation done by someone who "knows the rules") is much more thoughtful than innovation that isn't; this is especially true in music.

I realize that last sentence sounded a bit curmudgeonly so I'll give an example: Despite my penchant for Old Time music, I'm obsessed with Chris Thile, who comprised 1/3 of Nickel Creek and formed the Punch Brothers, a band I've seen at least 10 times live (and who, in a career move I could never have predicted, recently took the reins of "A Prairie Home Companion"). He is undoubtedly the most innovative mandolinist (and really, musician) I've ever heard; its pretty easy for me to call him a genius and the MacArthur foundation agrees with me (Thile got a $500,000 "genius" grant in 2012 and spent a good chunk of it on a new mandolin....which is exactly what I would have done in his shoes!). That being said, Chris Thile didn't reinvent the mandolin by just picking up the instrument on day 1 and "doing his own thing." Rather, he spent a lot of time learning the rules (i.e., getting to know the Bluegrass style and repertoire). If he jumped into a jam tomorrow, I'm willing to bet he'd know the tunes that were called and he'd be able to do a convincing imitation of Bill Monroe when it was his turn to take a break. As a result of this immersion, you can hear Bluegrass in Thile's approach to this day no matter how "out there" the Punch Brothers go (....and they go out there...). For instance: Bluegrass mandolins traditionally "chuck" (a percussive move not unlike a banjo "cluck" in sound) on the back beats in a jam. By emphasizing the backbeats, the mandolin player drives the band forward in the same way a snare drum drives a rock band forward. Thile takes the percussive role of the mandolin to new heights in Punch Brothers, chuck-ing out complex syncopation behind his band-mates as they somehow faithfully create Radiohead's Kid A on acoustic instruments. Ideas like this don't spring fully formed from a void: there's something in the type of innovation occurring here that is respectful of tradition. However, this approach is undoubtedly Chris Thile's own style nonetheless. For all of my bloviation (above), this post concerns something fairly mechanical in nature: the right hand motion of a clawhammer banjo player. I'll break down the "rules" that govern the right hand motion of a clawhammer banjo player (...as I understand them) and then give examples of when I choose to break these rules, which will hopefully give you ideas about how to make similar decisions in your own playing. Step 1: Learning the "rules" of the right hand What really attracts people to clawhammer banjo is the driving rhythm. If you watch the right hands of highly-rhythmic players like Ralph Stanley and Grandpa Jones, you see that they move like unstoppable freight trains. Melody notes seem to pop out of this right hand motion as a matter of course; the right hand doesn't stop to find them. This constant motion can be called "right hand stride." While its easy to identify right hand stride in the players I just mentioned, clawhammer banjo players using a variety of approaches keep right hand stride going by default as well. So what are the rules governing right hand stride? Rule 1 for maintaining right hand stride: The index finger of the right hand moves towards the strings on every beat; the thumb never plays notes on the beat. Before elaborating I'll give a bit of theory - this may be a little simplistic but I feel that its useful to build on so please bear with me - let's define the word "beat" : ) For our purposes, we can think of the beat as an imaginary constant pulse that permeates a given piece of music. While it doesn't need to be played out loud during a tune, every player should have this pulse going in their head while playing; musicians play together without a metronome by having the same perception of the beat of a tune; they mentally lay this beat down behind the notes, regardless of whats going on melodically. Most of the tabs I write are in 4/4 time; this means that there are 4 beats in every measure and that if a measure were filled with only 4 quarter notes, these notes would co-occur with the beats. I always indicate the beat above the staff in my tabs; the spaces with numbers (i.e. 1, 2, 3, and 4) are beats, the spaces with "+" are subdivisions of the beat (half-beats), useful for counting. Here's an example:

Figure 1 - A no-frills A part walk up to "Spotted Pony" stolen from my previous post (here). All notes should be played with the index finger of the right hand to maintain "right hand stride."

You can count the beat (and half beats) for the two measures above the staff as follows: "One and two and three and 4 and, one and two and three and four and." In the example shown in Figure 1, notes occur on the beat and nowhere else. Rule 1 (above) says that your index finger should be moving towards the strings on every beat; it therefore makes sense to use your index finger to play every note above. If some of these notes were exchanged for brushes you'd still use your index finger to play them because they are on the beat.

Importantly, Rule 1 should not be interpreted to mean that you have to play something on every beat. What if we took out the notes on beats 2 and 4 in the above tab? Would your hand just stop moving in between notes? Not if you want to maintain right hand stride! Rule 1 says that you've still got to move your index finger towards the strings on these "empty" beats, but you're free to move your hand past the strings and insert "ghost" notes in these spaces (intro to "ghost" notes here, about halfway down). In fact, the whole reason for the existence of ghost notes is to keep right hand stride going while decluttering your playing. So, how do we play notes on the "and's" between beats? Rule 2 for maintaining right hand stride: The index finger is never used to play notes between beats; these notes should be played with the thumb of the right hand, with a left hand pluck, or by hammer-ons/pull-offs from notes played on preceding beats. In Figure 1 we played every note with the index finger of the right hand because these notes were on beat. How do we use Rule 2 to deal with notes on "and" beats? Check out Figure 2:

Figure 2 - constant double thumbing in the A part walkup from "Spotted Pony."

Most clawhammer players intuitively know to play the 5th string with the thumb in the example above. In fact, the 5th string is often actually referred to as the "thumb string." But, lets spend a second putting ourselves in the mindset of a true novice looking at Figure 2: in theory, you could play 5th string notes with your index finger (I know that Frank Lee of the "Freight Hoppers" does this occasionally) and a novice may be tempted to play every note above with the index finger. However, playing this way would mean that their hand would have to move twice as fast to play Figure 2 as it did to play Figure 1; this would be a clear break of "right hand stride" and I think it would be difficult to accomplish when playing up to speed. Rule 2 tells us that we should find another way to play these notes. Since they are on lower strings than the notes preceding them, the thumb is the go-to option in this case. In fact, we can codify how to play notes on the half-beats by expanding rule 2 as follows:

Rule 2a) if the note on an "and" beat is on a lower string than the preceding note (or if the preceding beat contains a brush, cluck, or ghost note) this note should be played with the thumb of the right hand, or by plucking the string with the left hand. Rule 2b) if the note on an "and" beat is at a higher fret of the same string of the preceding note, this note should be played with a hammer on. Rule 2c) if the note on an "and" beat is at a lower fret of the same string of the preceding note, this note should be played with a pull off. Rule 2d) if the note on an "and" beat is on a higher string than the preceding note, this note should be played by plucking the string with the left hand. With these 2 simple rules (..okay, rule 2 is kinda long as expanded above...), we can play simple bum-ditty banjo, dial back our brushes by inserting ghost notes, play constant double thumbing, and even play highly melodic banjo lines. While these approaches sound quite different, they're all fairly easily accomplished without breaking right hand stride: the index finger of your right hand is always "counting the beat" by moving towards the strings (whether they hit them or not), the thumb of your right hand is sometimes noting "and" beats (either with 5th string pulls or drop thumb), and you're filling in remaining melodic blanks with hammer-on's, pull-offs, and/or left hand pulls. Using the Rules to craft an arrangement of a tune: Just to bring it all together, lets check out the following tab for the first line of "Temperance Reel," a particularly notey tune of Irish descent that I play in Old G (gDGDE) tuning:

Figure 3 - The first line of "Temperance Reel" in Old G (gDGDE) without any indication of how to play it with your right hand. Note that a full tab and video of this tune are available in a previous post (here).

The tab above looks dauntingly-melodic. Obviously, we can't get this thing up to speed by playing everything with our index finger so we turn to Rules 1 and 2 to figure out how to play it "in stride." Rule 1 guides us on how to play the on beat notes (those with the numbers 1-4 above them): these all get played with the index finger. So, we've just got to figure out how to play all the notes on half beats ("and" beats). For simplicity, I'll just list every beat and half beat along with which right hand approach should be used to play them according to rules 1 and 2 below:

Playing Figure 3 "by the rules" Measure 1, Beat 1: Index (Rule 1) Measure 1, Beat 1 +: (empty - I just rest my thumb on the 5th string for this beat) Measure 1, Beat 2: Index (Rule 1) Measure 1, Beat 2 +: Drop thumb (Rule 2a) Measure 1, Beat 3: Index (Rule 1) Measure 1, Beat 3+: Hammer on (Rule 2b) Measure 1, Beat 4: Index (Rule 1) Measure 1, Beat 4+: Hammer on (Rule 2b) Measure 2, Beat 1: Index (Rule 1) Measure 2, Beat 1+: Drop thumb (Rule 2a) Measure 2, Beat 2: Index (Rule 1) Measure 2, Beat 2+: Pull off (Rule 2c) Measure 2, Beat 3: Index (Rule 1) Measure 2, Beat 3+: Drop thumb (Rule 2a) Measure 2, Beat 4: Index (Rule 1) Measure 2, Beat 4+: Hammer on (Rule 2b) We can cover all of the notes above without ever having to break right hand stride! Here's how the first line of "Temperance Reel" looks as a result:

Figure 4. The first line of "Temperance Reel" with hammer on's, pull off's, and drop thumbs added to maintain right hand stride. Slurred notes indicate a hammer on or pull off; bracketed notes are meant to be played with the thumb.

So, we know the rules for maintaining right hand stride, and we can even use them to make arrangements of complex melodies. As an aside: I very rarely opt for left string pulls in my playing - as of now they just don't come naturally to me in a melodic context and when I try to use them they really stick out. I know they can be pretty useful tools (especially if you've got to go up more than one string on a half beat) but I just don't need them that often as of now. Perhaps this will change one day : )

So now that we've "learned the rules" that govern right hand stride, lets break them! Step 2: Breaking the rules! "Angeline the Baker" is one of the more common D tunes out in the world. That being said, playing the melody faithfully to your average fiddler's version can be a bit complicated for a beginner. Before getting too much further, lets take a look at the first line of the A part to show you what I'm talking about. It should be noted that this is one of those tunes of which people will argue about which part is the A part: for the record, I now think of the low part as the A part, but when I first learned the tune I was firmly in the other camp (kinda can't even imagine it now...)

Figure 5. The first line of the A part of "Angeline the Baker" with words that correspond to each note. To be played in double D tuning (aDADE)

The fiddle tune we call "Angeline the Baker" comes from Stephen Foster's vocal tune (i.e. song) "Angelina Baker" so it makes sense that you still hear people singing this one (though "Angelina" seems to have shifted to "Angeline the" at some point). I lean towards Crooked Still's take on the tune; in my opinion Aoife O'Donovan has one of the best voices in music today and Rashad Eggleston's cello playing is fantastic. I've put the words Aoife sings below the notes in Figure 5. Rather than subjecting you to my singing to demonstrate the phrasing, I'll play an example on the piano (you're welcome : ).

The rhythm we're shooting for in the melody of "Angeline the baker" repeated 4 times on piano (tabbed for banjo in Figure 5; the final "bum ditty" is not played here).

So how would we play Figure 5 "by the rules?" See Below

Playing Figure 5 ("Angeline the Baker") "by the rules" Measure 1, Beat 1: Index (Rule 1) Measure 1, Beat 1 +: (empty - I just rest my thumb on the 5th string for this beat) Measure 1, Beat 2: Index (Rule 1) Measure 1, Beat 2 +: (empty - I just rest my thumb on the 5th string for this beat) Measure 1, Beat 3: Index (Rule 1) Measure 1, Beat 3+: (empty - I just rest my thumb on the 5th string for this beat) Measure 1, Beat 4: Ghost note (Rule 1) Measure 1, Beat 4+: Drop thumb (Rule 2a) Measure 2, Beat 1: Index (Rule 1) Measure 2, Beat 1+: (empty - I just rest my thumb on the 5th string for this beat) Measure 2, Beat 2: Index (Rule 1) Measure 2, Beat 2+: (empty - I just rest my thumb on the 5th string for this beat) Measure 2, Beat 3: Index (Rule 1) Measure 2, Beat 3+: (empty - I just rest my thumb on the 5th string for this beat) Measure 2, Beat 4: Brush with Index (Rule 1) Measure 2, Beat 4+: thumb (Rule 2b) Here's the resulting tab:

Figure 6: Playing "Angeline the Baker" by the rules. To be played in double D tuning (aDADE)

Bracketed note is meant to be played with a drop thumb.

So, we can play "Angeline the Baker" by rules 1 and 2, which allows us to maintain right hand stride. But, its a tall order for a beginner (or even a seasoned player!). First off, the lack of a note on beat 4 of the first measure necessitates the use of a "ghost stroke" which many people find awkward to begin with. Still, many players can handle a ghost stroke in isolation, but this is actually a ghost-stroke-to-drop-thumb, combo (an even tougher sell). Finally, the drop thumb is followed by an index strike on the same string, a move that always feels a bit crowded to me. Once again, this can be done, but many players (including myself) choose not to.

Surprisingly, some players avoid all this ruckus by altering melody: if you move the offending melodic bits over a half beat things become a lot easier on the banjo player. Here's what I'm talking about:

Figure 7. The first line of "Angeline the baker" with a melodic shift to allow for easier playing.

To be played in double D tuning (aDADE)

As you can see, the offending melody note shifts over from the "4+" half beat of the first measure to the "1" beat of the second measure. The next note is an easy hammer on. This approach necessitates some filler for the last bit of the first measure: I just added a "brush-thumb" in to complete a "bum ditty" that starts on beat 3. By doing this, we've changed the core melody as follows:

Altered melody of "Angeline the baker" repeated 4 times (tabbed for banjo in Figure 7; "bum ditty's" are omitted here).

I guess it sounds okay, but don't try to sing along : ) Also, it may subtly clash with a fiddler; since I like playing duets with a fiddle, this has the potential to really stick out...not ideal. Luckily, we really don't have to pick between making melodic compromises (i.e. playing Figure 7) and potentially train-wrecking to avoid breaking rules (i.e. playing Figure 6). This is where I simply Ignore the rules and play Figure 5 as follows:

Playing Figure 5 ("Angeline the Baker") by breaking the rules! Measure 1, Beat 1: Index (Rule 1) Measure 1, Beat 1 +: (empty - I just rest my thumb on the 5th string for this beat) Measure 1, Beat 2: Index (Rule 1) Measure 1, Beat 2 +: (empty - I just rest my thumb on the 5th string for this beat) Measure 1, Beat 3: Index (Rule 1) Measure 1, Beat 3+: (empty - I just rest my thumb on the 5th string for this beat) Measure 1, Beat 4: Pause your right hand (break stride) Measure 1, Beat 4+: Index (rule violation) Measure 2, Beat 1: Hammer on (rule violation) Measure 2, Beat 1+: Pause your right hand (break stride) Measure 2, Beat 2: Index (Rule 1) Measure 2, Beat 2+: (empty - I just rest my thumb on the 5th string for this beat) Measure 2, Beat 3: Index (Rule 1) Measure 2, Beat 3+: (empty - I just rest my thumb on the 5th string for this beat) Measure 2, Beat 4: Brush with Index (Rule 1) Measure 2, Beat 4+: thumb (Rule 2b) As you can see, my transgressions are unashamedly presented in bold above : ). Really I start breaking the rules before even sounding a note by avoiding a "ghost note" on the 4th beat of the first measure. What do I do on the 4th beat? Just kind of sit there really...it feels weird at first but you get over it. Having "reset my hand" for half a beat, the next two notes (a cross measure open string to 2nd fret hammer on) really don't feel that odd; its easy to pretend like I'm "on beat" for this move. Finally, I spend the 1+ half beat in the second measure slowly moving back "into phase" in preparation for the rest of the tune. The first time you try this it will feel (and sound) awkward, but eventually it can become second nature. Here's the resulting tab:

Figure 8. Breaking the rules in the first line of "Angeline the Baker." To be played in double D tuning (aDADE). Slurred notes indicate a hammer on. A star above the staff indicates the use of an index finger in an unexpected place.

Here's me on banjo playing figure 8.

Playing Figure 8 on the Buckeye (double D tuning; aDADE)

Not too terrible, right? Once I embraced a willingness to break the rules governing right hand stride, I found that a lot of tunes that seemed like they "just didn't work for clawhammer" in the past came into my grasp - next week I'll share a tab for one!

Thats it for now! Hope you have a great Thanksgiving!

One thing I love about Old-Time music is that there doesn't seem to be a formula for what constitutes a "real" Old-TIme band. While groups will typically include fiddles, banjos, guitars, basses, and sometimes mandolins, no one would use the presence of cellos, dulcimers, harmonicas, accordions, concertinas, spoons, washboards, tin whistles, cajons, or musical saws, to question the "authenticity" of an old time band (yes, I heard all of these instruments in jams while walking around Clifftop this year : ). In years past (and today), people likely played "fiddle tunes" on whatever instruments were available; these eclectic variations in instrumentation help make Old-Time such a big tent, in which you're free to find your own niche for expression.

On that note of inclusiveness: enter the baritone ukulele! While these instruments are tuned like the top 4 strings of a guitar, its a mistake to think of baritone uses as somewhat-limiting diversions for guitarists. The wide string spacing and short scale length make these instruments unique in their own right; while I can play most of the stuff I play on the baritone uke on guitar, the music loses a lot in tone and fluidity in the transfer. On our first wedding anniversary, my wife surprised me with this beautiful baritone uke (pic below) and its become my go-to couch buddy, often even at the expense of the banjo!

A picture of the beautiful slot-head baritone uke that my amazing wife bought at Elderly for our first anniversary. Hard to say I haven't found my soul mate (yes, I mean my wife, not the uke).

Because they're pretty much constantly meandering through my head, absent-minded noodling on my new toy inevitably wandered towards fiddle tunes, and I came to a crossroads: Do I treat the uke like a tiny quiet banjo or do I treat it like a uke?

On treating the baritone uke like a banjo: You'll notice that standard baritone uke tuning (DGBE) is pretty close to "open G" (gDGBD) on a banjo, but with the 5th string removed and the 1st string tuned down a whole step. In fact, the baritone uke can be tuned to 5th string-less variations of all of my commonly used banjo tunings; in this configuration, I already know hundreds of fiddle tunes. It can be played clawhammer style, though the lack of a 5th string to pluck/rest on takes some getting used to; you can put the 4th string in this role when the melody is on strings 1-3, but it does sound a little odd and you quickly get a little bit of dysphoria when the melody veers low. As an aside, standard ukes (i.e.tenor, soprano, and concert ukes) have a re-entrant tuning that banjo players may have a bit of comfort with: gCEA. Clawhammer comes pretty naturally with a "high" string on the bottom, and you can find a bunch of clawhammer uke videos online. Once again, this works for tunes that stick to the high strings; when handed a standard uke, I can quickly pull out a clawhammer version of "Sandy boys" in C that sounds pretty solid : ) However, I have plenty of banjos and don't really need a "fake banjo" without a 5th string. To me, it s more fun to treat the uke like its own thing and learn some fiddle tunes in standard baritone uke tuning. Treating the baritone uke like a uke I decided I'd play D and G tunes in standard tuning and A tunes with a capo, pretending like they're G tunes (most of the time I don't bother to capo for A tunes since I'm playing alone). My clawhammer roots make me dissatisfied with unaccompanied melody; I wanted to bring backing chords into my uke playing as well. Since standard baritone uke tuning is not an "open tuning" (i.e. it doesn't make a pretty chord when strumming the open strings), this approach requires me to be constantly holding down a chord while I play. The fact that the uke is a 4 string instrument makes the acrobatics involved in this approach a little less intimidating than what travis-style guitar pickers like Chet Atkins do. A G major chord (A major if you capo) is available with just one finger (0003); a D major chord takes a bit more effort (0232). However, you don't have to hold down all of a chord if you're not using all of it, and notey sections of tunes require no backing whatsoever. Right hand concerns: Fingerstyle playing on guitar seems a little intimidating. While clawhammer has "rules" you can impose on an arrangement (e.g. index on down beats, thumb on up-beats; bum-ditty framework throughout), finger style guitar has always looked a little more "free-wheeling" as an observer....this is probably because I've never really looked in to how to play it properly : ) I decided to take my right hand inspiration for the baritone uke from what little I know about 2 finger "thumb-lead" banjo playing. 2 basic moves in this style are shown in Figures 1 and 2 (below). Note that "bracketed" notes in the following tabs are meant to be played with the pointer finger (actually, I use my middle...) and all other notes are meant to be played with the thumb.

Figure 1 - A 2-finger "thumb-lead" banjo "bum-ditty" rhythm (aDADE tuning)

Figure 2 - A 2-finger "thumb-lead" banjo "pinch" rhythm (aDADE tuning)

I think of "thumb-lead" style as backwards clawhammer. If you play Figure 1, you get the "bum-ditty" rhythm, but the 5th string pull is on the "di" instead of the "tty." Sounds pretty cool though, and you're still following the fiddle shuffle pattern. Figure 2 is base on the "pinch," where a single "long" string is picked in concert with the 5th string; there's not really a clawhammer analog for this but bluegrass banjo players do it a lot. The pinch is a little more "boom-chick" in feel and ties you pretty well to a guitarist. To make an arrangement in either of these styles, you simply work these patterns "around" the melody notes to fill empty space as you would for making a clawhammer arrangement. Examples from (wait for it!) the A part walk up of "Spotted Pony" below (context):

Figure 3 - A 2-finger "thumb-lead" banjo "bum-ditty" version of the A part walkup in "Spotted Pony"

(aDADE tuning)

Figure 4 - A 2-finger "thumb-lead" banjo "pinch" version of the A part walkup in "Spotted Pony"

(aDADE tuning)

Obviously you have to remove the 5th string pulls to apply these approaches to the baritone uke. I do this by simply putting an internal string pluck in the place of the 5th string in the tabs above. Baritone uke versions of the A part walk up to "Spotted Pony" (using the "bum ditty" and the "pinch") are shown below. Once again, I have to hold down the relevant notes for backing chords the whole time in addition to fretting melody notes to make this work. In this case, I chose to suggest D major chords for the first measure and a half, then a G major chord for the last half of the 2nd measure (note that I sometimes put an A major chord in the 2nd half of the first measure). I got to cheat a bit by ignoring the 1st string since I don't use it here (i.e. I fret a D major as follows: 0230).

Figure 5 - A 2-finger "thumb-lead" baritone uke "bum-ditty" version of the A part walkup in "Spotted Pony" (DGBE tuning)

Figure 6 - A 2-finger "thumb-lead" baritone uke "pinch" version of the A part walkup in "Spotted Pony"

(DGBE tuning)

Coleman's March on the baritone ukulele

If you've been paying attention to this blog, you know I love the fiddle tune "Coleman's March" (example). To cap off this post, I thought I'd play a finger style chord/melody version of "Coleman's March" on baritone uke. First, the audio:

"Coleman's March" on my baritone ukulele - pretty sweet-sounding instrument, huh?

For those of you who have, or would like to get, a baritone ukulele (even the nice one's are quite affordable!) I've written out a tab for you to play along:

----------------- Click here for a tab of "Coleman's March" for baritone ukulele ----------------------- Though this version applies the "bum-ditty" approach from Figure 5, you could easily convert this tab to a "pinch" version (i.e. more like what's presented in Figure 6) without too much work as well. Note that I used brackets to indicate notes that should be played with the index (or middle) finger here as well - all other notes should be played with the thumb. Also, I found a couple of pretty nifty chord substitutions (check out my chord substitution post here) at the beginning of the B part: rather than playing a D major chord for the first measure and an A major chord for the second measure, I play a B minor chord for the first measure and F# major chord for the second measure the second time through. Tab for this substitution is given at the bottom of the second page; definitely makes the tune a bit more interesting! Thanks for reading along and indulging my exploration outside the "normal" bounds of old time instrumentation : ) My only regret is that finger style baritone uke is a bit too quiet to play in a group setting, though it may be loud enough to play with just a fiddler. If I go further down this road, I may look into something louder: a baritone banjo uke, a nylon-strung chicago-tuned tenor banjo, or even a resonator-guitar-like model for volume. For now, I'm pretty content to plunk around on my couch : ) In last week's post (Extreme ghost noting in "Yew Piney Mountain"" - available here), I posted tab and audio of an extremely crooked version of the West Virginia tune, "Yew Piney Mountain." While I got the inspiration for my arrangement from Chance McCoy's fairly-recently-recorded solo fiddle version (off of his 2008 album "Debut" - post about that album and other New Old time albums here) just about everyone who plays this tune seems to treat it a little differently. Melodic phrases can be recognized from version to version, but certain chunks may be removed or added by fiddlers to make the tune their own. While we treat source recordings as gospel for how a certain fiddler played a tune, I often wonder if these bouts of crookedness in "Yew Piney Mountain" may have changed if the tune were recorded by the same fiddler on a different day of the week : ) As someone who loves to play in groups, all of these versions of "Yew Piney Mountain" can create a bit of a barrier to participation in a jam setting. While all tunes vary a bit, players can usually play different versions of "top 40" tunes together without too many sour notes and more experienced players can easily alter their versions on the fly to match others in the group; different versions of "Yew Piney Mountain" don't typically play well together however and the amount of time it would take to figure out the nooks and crannies of someone else's version could easily bring a jam to a halt. Hence, the need for a "festival version" of "Yew Piney Mountain" a couple of which I'll provide tabs for in a bit... First, a definition: when I refer to a "festival version" of a tune, I simply mean a version that represents the "musical average" of the versions of that tune you'd find out in the wild (and on field recordings). For this reason, festival versions will tend to be a little less notey and a little more squared off (i.e. less crooked) than many regionally-specific versions of a tune. I'll say right here that many people dislike the existence of "festival versions" of tunes, arguing that they represent a tendency towards homogenization of what was once a highly regional art form. Thought I can understand this attitude, I'll counter it with the following: festival versions of tunes are not usually created, they just occur when people from different places meet and play. In that sense, they seem like a pretty organic next step in the evolution of Old-Time music; since globalization, and the cultural homogenization associated with it, is only going to increase as time goes forward, we may as well embrace "festival versions" of tunes as somewhat "authentic" musical creations in their own right. Furthermore, I think that "festival versions" serve as great entry points for diving into a tune; there is no reason to only play the "festival version" of a given tune, but it sure helps to have a simple stream-lined version of a tune like "Yew Piney Mountain" down for comparison before you try to pick out the nuances of a fairly obscure version. In this way, "festival versions" serve as teaching aides for more sophisticated investigation of a tune. -------------------------------------------- Rant, if that was a rant, over : ) ------------------------------------------- A bit of context for the "festival versions" of "Yew Piney Mountain" I'll present here: The first version comes from "Mando guy" (read about him in my "Chord Substitutions" post here); he called "Yew Piney Mountain" in our late-night jam towards the end of Clifftop this year. Given my own bizarre version of this tune (and the others I'd heard), I was a bit worried that I'd never catch his version when he started to play - however it turned out to be his contra-dance-friendly version, which I was able to match fairly quickly, while still retaining much of my melody. Its absolutely recognizable as a variant of "Yew Piney Mountain" when compared to most tunes that go by that title, but easier to pick up on the fly (and keep up with) than most of them as well. This one is absolutely squared off, but I've heard other jam-friendly versions that still have an extra beat or two at the end of the B part. The second version is simply a Mixolydian variant of the first version (if you don't know what I'm talking about, read my blog post on "modes" here). While many versions (including my own crooked version) are solidly in A minor (aka Aeolian) employing a C natural (minor 3rd), I've heard some Mixolydian takes (which still lean on a flattened 7th, but include a C#/major 3rd) on this tune as well. Fiddlers and fretless banjo players may even choose to keep one's ear guessing by playing a micro-tone between the notes and some players may switch modes by changing the note they choose mid tune....I thought that including both minor and Mixolydian versions (which are identical other than the "C" of choice) would provide you with enough options to cover all these bases : ) Your index finger has to do just bit of extra work to cover the C#'s in the A part. Without further ado....here are the tabs: Hopefully these are just a bit more jammable than the last version I passed on last week - hope you have fun with them!

This past Friday, I had a really nice 3 person jam (banjo, guitar, fiddle) at the home of a local fiddler. We covered some interesting ground tune-wise and he let me play his 6 string banjo for a bit; to clarify, this banjo had one extra bass string added to the normal 5 string configuration (i.e. it was not a guitar banjo). We played a couple of D tunes with it tuned aADADE (basically Double D tuning with an added low A string)....it was just amazing!! I was able to play low octaves of melodies and harmonies on the low A string right off the bat. Hopefully I'll get to play thing thing more in the future....and maybe get one of my own some day : ). |

-----

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed